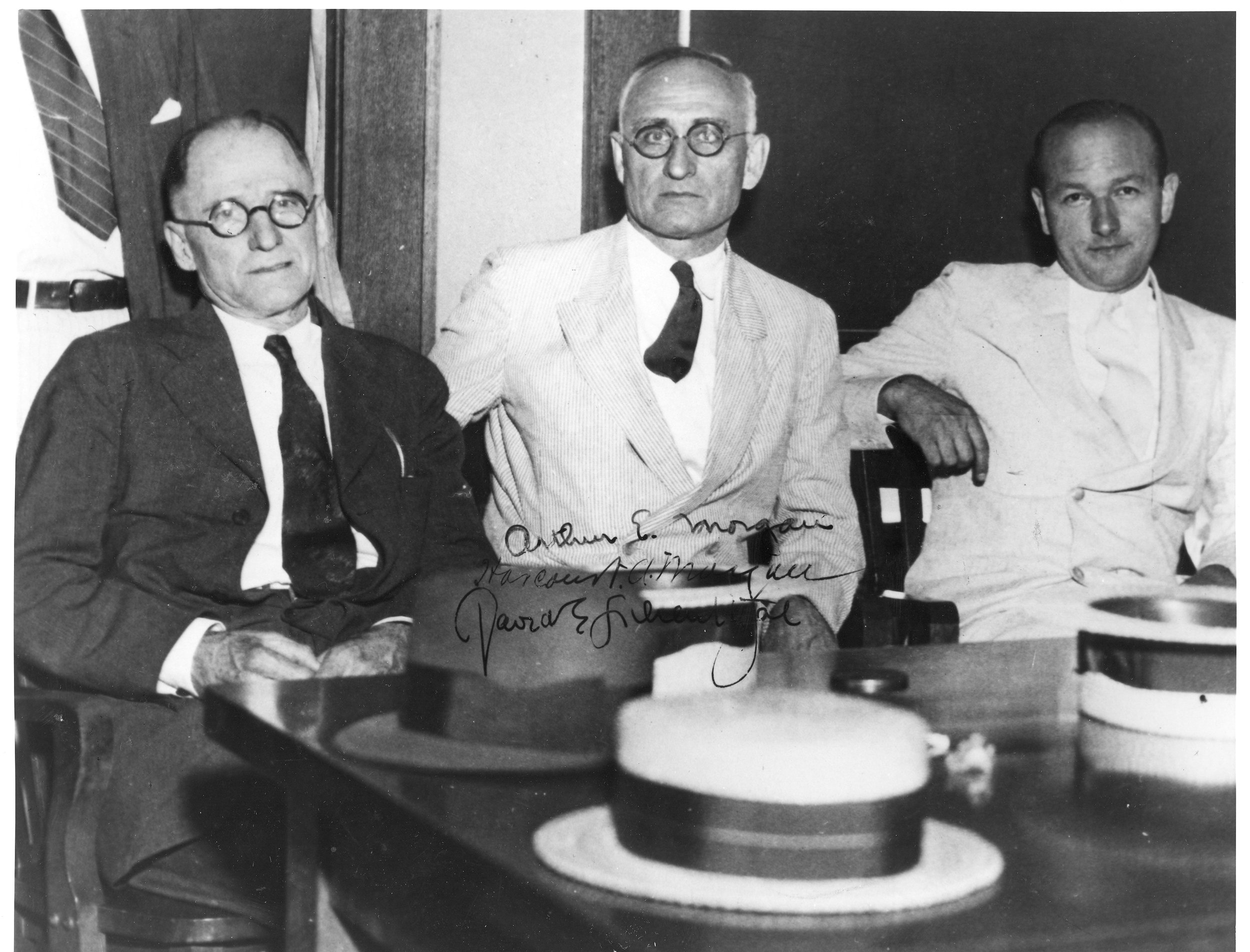

Above: Arthur E. Morgan, center, saw TVA as little less than a means of reinventing civilization. He was to prove far more adept at technical engineering than social engineering. But to the extent that TVA was and is an ongoing visionary experiment, the original impetus came from him.

Arthur Morgan — The Visionary

Written as part of the Tennessee Valley Authority Heritage Series

Arthur E. Morgan’s farsighted vision and exacting discipline built a system of dams and social management that changed the lives of millions of Valley residents. But what he couldn’t manage was human nature.

Arthur E. Morgan was one of the most influential Directors of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and one of the most controversial. Perhaps he was also the one you’d be most likely to remember if you saw him in the street.

At 6 foot 2, he was as thin as Ichabod Crane; behind his black-rimmed spectacles his eyes had an intense and critical look that gave him the aspect of a startled predatory bird. Morgan caught people’s attention, both with his appearance and with his unusual ideas.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt hired him in 1933 as the first Chairman of the TVA Board, Morgan was famous for two things that might seem to have nothing to do with each other: building efficient dams for flood control, and believing in the perfectibility of humankind. In TVA he saw his chance to bring the two together.

The idealistic Morgan’s most evident achievement was literally cast in concrete: the TVA dams.

A brilliant technical manager, Morgan launched a string of dam-building projects that almost always came in on time and under budget. But the dams, he believed, were only part of a larger effort to transform life in the Tennessee Valley. Morgan saw TVA as little less than a means of reinventing civilization. He was to prove far more adept at technical engineering than at social engineering. But to the extent that TVA was and is an ongoing visionary experiment, the original impetus came from him.

He grew up in St. Cloud, Minnesota, a small town beside the Mississippi River. He was the child of parents of nearly opposite temperaments: an easygoing father who was often absent because of his work as a surveyor, and a religiously zealous mother. Morgan has been described as inheriting both his father’s scientific mind and his mother’s moralistic heart.

Unable to get into college, he found work cutting timber in Colorado during the 1890s. He was one unusual lumberjack. It’s said that he quit a job when he learned that the lumber he was producing was bound for a new gambling saloon.

Returning to Minnesota, Morgan helped out at his father’s surveying concern. The work gave him an education and an opportunity to solve engineering problems, especially those concerned with drainage. By the time he was 30, he had earned a reputation as one of the nation’s best field engineers.

Then came the devastating Miami River flood of 1913, which killed more than 300 people in Ohio. The state hired Morgan to prevent future disasters, and he did so with comprehensive planning and the establishment of what he called a conservancy district—steps that went far beyond conventional flood-control methods. He also tried to organize the dam-building workers into small communities, putting up houses for them and offering them instruction in sound values.

Thus the dam engineer who never went to college developed a second reputation as an educator. In 1921, the struggling Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, hired Morgan as its new president. Under his leadership the school blossomed, pioneering a co-op plan in which the students combined work and study. Morgan’s goal was to produce philosopher-engineers energized by an “enlightened moral enthusiasm.”

In 1933, he was astonished when President Roosevelt invited him to the White House and offered him the chairmanship of TVA. “I like your vision,” said FDR. The visionary set about launching this wholly new enterprise, doing much of the practical work himself.

Although Morgan remained an idealist, his most evident contributions to TVA were literally cast in concrete. As chief engineer, he headed the staff that built the parts of TVA people could point to—especially TVA’s flagship project, Norris Dam, and the dams that followed, including Wheeler and Pickwick. His designers and engineers even built a model community at Norris to house the workers who were building the dam.

As general manager of TVA, Morgan handled the finances, exhibiting his famous intolerance for waste. He directed TVA’s early educational programs, which included a library service that brought books to isolated Valley communities and a progressive high school in Norris.

He directed TVA’s conservation efforts, its forestry and soil-erosion programs, the projects that developed recreation areas and made Valley waterways more navigable. He took charge of regional planning and social and economic organization. To Morgan, comprehensive, large-scale planning was the single most compelling aspect of TVA’s mission. He was especially fascinated by Norris, a community that exemplified his passion for planning.

The task of integrating TVA’s diverse undertakings was another part of his job, and for him it was one of the toughest. Often Morgan simply couldn’t find a way to integrate his own strong personality with those of his fellow Directors, Harcourt Morgan (no relation) and David Lilienthal.

Chairman Morgan and Director Lilienthal clashed most often, and on issues as important as how to distribute the power produced by TVA. Morgan proposed that TVA enter into an agreement with the existing private utilities to distribute electricity; Lilienthal argued that it would be better to let a network of local public utilities handle the job. Ultimately Morgan just didn’t like Lilienthal, whom he considered a political opportunist. He asked FDR not to reappoint the young Director.

In 1936, their dispute went public. Morgan eventually accused Lilienthal and others at TVA of corruption and abuse of power. His charges prompted a long and complicated congressional investigation. Asked in 1938 to substantiate the allegations, he declined. President Roosevelt suggested that Morgan resign, but he refused to do that. So the president fired him.

Congress exonerated Lilienthal, who went on to a highly successful tenure as TVA Chairman during World War II. It might have seemed to many that Morgan, 60 years old and with a history of medical problems, was at the end of his career.

But he was to live for nearly four more decades, publishing a string of thoughtful books on topics ranging from the ideas of Sir Thomas More to dam-building by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He released his last work, “The Making of TVA,” in 1974, just a year before his death at age 97.

In it he documented the creation of the dream he had done so much to shape, but had seen fulfilled only by others.