On the lake: Navigating a sense of place

Sunrise over Cleveland from Huntington Beach, Bay Village, Ohio. (Photo by Erik Drost, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons)

This article continues our series on sense of place as we, at Agraria, explore the scale of our work and service to our local, bioregional and global community.

By Megan Bachman

“If you don’t know where you are, you don’t know who you are.” — Ralph Ellison, from

“The Invisible Man”

I grew up near Lake Erie, outside of Cleveland. As a kid I would ride my bicycle up to the beach, the one with cigarette butts mixed into its hard, rocky sand. We went there to watch the sunset, swim (when it was safe to do so), eat frozen bananas, and climb on boulders. Especially as I got older, it became more of a place for contemplation than recreation thanks to decades of careless pollution from nearby industrial and wastewater treatment plants.

Despite its problems, the lake loomed large in our lives. It was our true north, the feature to which we oriented ourselves, in both space and time. You could never get lost because you could always ride or drive north until you hit the lake. The lake was a calendar too. Changes were marked by when the lake froze over, when winds whipped up wicked waves and when it baked in the sun long enough to wade in.

So I always knew where I was relative to the lake, and I always knew when I was. Did Lake Erie also shape who I was? What is the connection between place and identity? And why does it matter?

Encountering Sense of Place

I never considered such questions of place until I was in my 20s and participating in a local discussion group called, “Discovering a Sense of Place,” through the Northwest Earth Institute. It was a new term to me, but one which immediately clicked on a gut level. I shared my memories of the lake and soon we were all speaking of our places as we would dear friends.

Rebecca Solnit writes that a sense of place is a "sixth sense,” “an internal compass and map made by memory and spatial perception together.” The “sense” may then be a feeling, a deep impression, that includes — and also transcends — all the senses. It exists, unique, to each person. It’s our map of the world, inscribed in the mind and heart.

Chunks of ice along the shores of Lake Erie. (Photo by Erik Drost, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons)

The lake commanded respect and taught humility, more like an elder imparting wisdom than an inanimate feature. I tended to personify the lake, its dramatic displays, and fickle moods — shifting from tranquil to tempest in an afternoon — and its capacity to foster life and bring death, like a creator deity. It was more than a place setting; there was a kinship there.

Considering one’s “sense of place” may be a wholly modern development. It wasn’t so long ago we humans lived entirely from our local environment, tapped into the flow of creation in ways my consciousness can scarcely comprehend. There was no pressing need for me to learn about the lake’s ecosystem, for my direct survival or economic benefit. We didn’t fish; mercury levels were too high. My parents’ jobs had no connection to that great body before us, though its strategic and resource-rich setting no doubt contributed to the area’s development. Lake effect snow and the resulting snow days was its most obvious contribution to my life.

Even still, the lake brought value to us in less quantifiable ways. Its rhythmic, ever-lapping waves were a source of solace, while the distant horizon invited big dreams and feelings of hope. It was a community gathering place, a place of informal pilgrimage and reverence. It was a teacher and a metaphor. Our subdivision ranch could have been anywhere, except that it was here. What did that mean?

Stranger in a strange land

Crafting a sense of place is always an exercise in meaning-making. When we aren’t given much material to work with, we have to do it ourselves. Our culture gives us many ways of centering ourselves in place and time. I pledged allegiance to a flag and knew I lived in America, a 200-year-old idea. I was given less orientation to my immediate surroundings. I was estranged from it, and with no guideposts, I was to navigate it on my own.

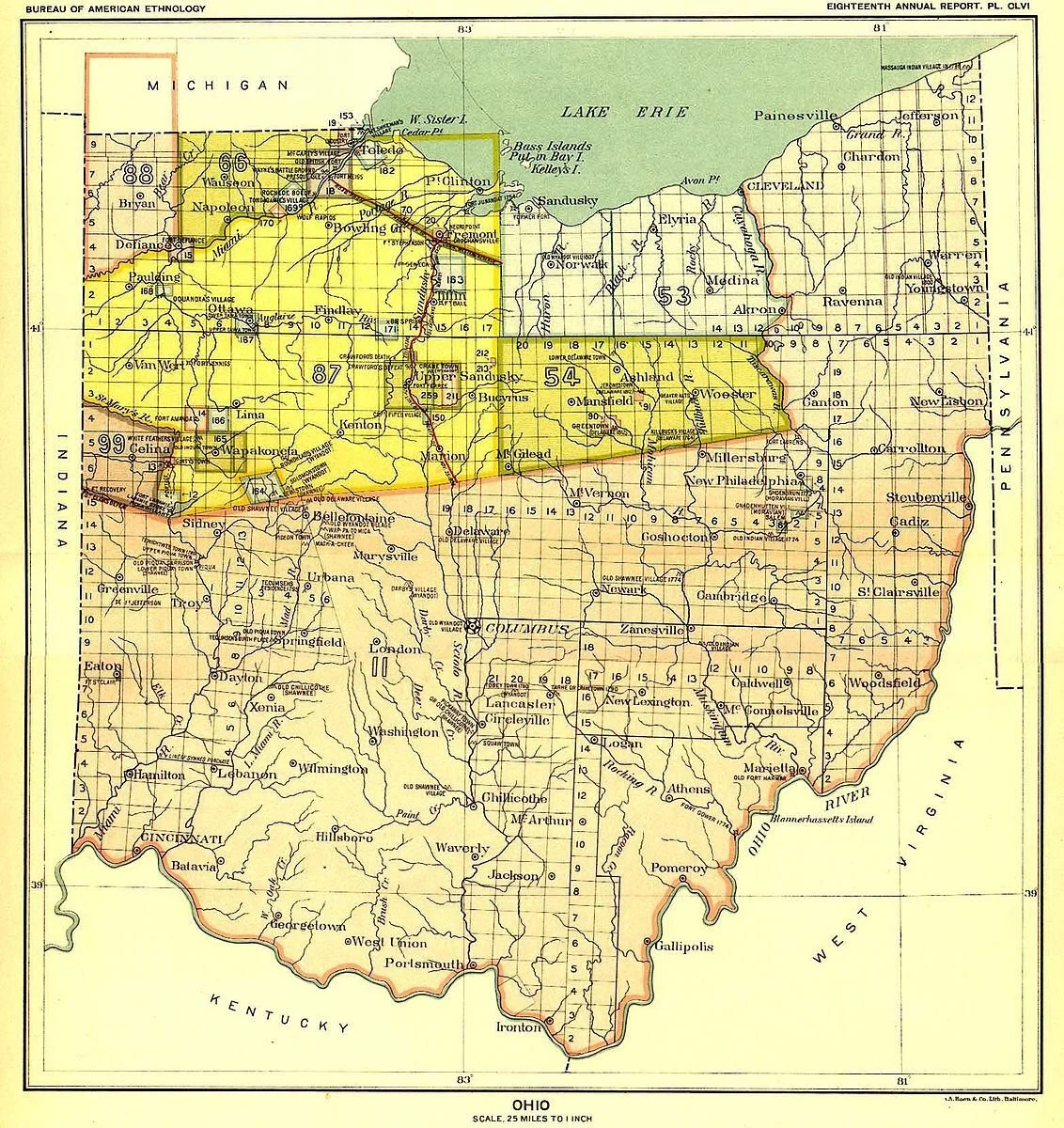

My family had only recently come to settle on this particular patch of earth. We were several generations away from farming, and the knowledge of living on and with the land had been lost before I was born. Moreover, the people who had long lived where I now did, and who the lake was named after, were largely erased from our history. Instead, my development, “Settler’s Landing,” was named for the early settlers of the town, white families who moved onto land “ceded” by the Ottawa, Potawatomi, Chippewa, Wyandot, Munsee, Delaware, and Shawnee Indians in an 1805 treaty.

A 19th century map by the Smithsonian Institution show the major Native American land cessions of what became Ohio. The author grew up in tract 53, near the Cuyahoga River, which was ceded in the Treaty of Fort Industry in 1805. (Public domain image)

Lake Erie was named after the Erie, an Iroquoian group that apparently lived in long-houses and cultivated the “three sisters” crops of corn, beans, and squash. Little history of the tribe survives — they were eradicated or assimilated during the battles between and among indigenous peoples and colonial powers in the 17th century — and none is taught to the schoolchildren who grow up on their ancestral lands.

Erie may be shortened from Erielhonan, which means “long tail,” a reference either to the raccoon tails tribal members wore, or the tail of a mythical underwater panther that loomed large in the cosmology of many Great Lakes-dwelling tribes. According to some depictions, it was a cross between a cougar and a dragon, covered in scales with spikes running along his back, which, as a child, would have both fascinated and terrified me. The God of my culture was not particularly tied to the land I was on; my religion’s spiritual home was in the Middle East, in contrast to the land’s prior inhabitants. Could those spiritual bearings be reclaimed?

Sense of place is a secular version of an earlier term, “spirit of place,” itself derived from the Latin, genius loci, Wade Davis writes in “Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World.” Genius loci is an ancient belief that gods or guardian spirits protect certain places, like mountaintops or natural springs. More recently, the spirit of a place is used to describe the unique or special qualities of a certain locale, often a place of obvious natural splendor, like Mount Shasta or the Grand Canyon.

Davis writes about how a spirit of place underlies a culture. One’s homeland can be understood as “the ecological and geographical matrix in which they have determined to live out their destiny.” A good word for it, matrix, coming as it does from the word, womb. “Just as a landscape defines character,” Davis adds, “culture springs from a spirit of place.” My current town, a couple of hundred miles south of the lake, is named for a nearby spring with long reputed healing powers — an idea foundational to our self-concept and enduring culture.

The eponymous Yellow Spring of Yellow Springs, Ohio. (Photo by Reilly Dixon, courtesy of the Yellow Springs News).

But what happens when that spirit is not named, acknowledged, or understood? Once lost, can it ever be restored? Some believe we simply cannot escape it; it is the water in which we swim. As writer D.H. Lawrence wrote in 1918, “All art partakes of the Spirit of Place in which it is produced.” Or is a sense of place constructed, even when drawing on the numinous, as in Solnit’s definition? My sense of place was not informed by any direct knowledge of the indigenous inhabitants of their lifeways. Was I missing something essential to understanding my community, to understanding myself?

Protecting what we love

Despite a massive hole at the center of my place-based consciousness, at the edges, I was in relationship with that lake, in my own way, stunted and incomplete as it may have been. I only realized the depth of my connection to the lake when I took a job during a summer break in college working to protect it.

We were a group of idealistic young environmentalists going up against a massive electric utility whose recklessness and greed threatened the entire ecosystem. As neighborhood organizers, we knocked on doors and raised money for our campaign to shut down a nuclear power plant on the lake 75 miles away that had nearly melted down a few years earlier when corrosion ate a football-sized hole in the reactor vessel head. Incompetence and neglect were to blame, and at one point a layer of stainless steel just 3/8ths of an inch thick was the only thing standing in the way of the lake’s ruin.

I was passionate about the work, and how it connected me to my home. Whether I was canvassing a wealthy stretch of lakefront property or a working-class neighborhood in the shadow of a factory, what tied together our community was a mutual care and concern for the lake. Perhaps it was a bit territorial for me to emphasize the need to defend our lake from them.

The Davis-Beese Nuclear Power Station in Oak Harbor, Ohio, then owned by FirstEnergy, now Energy Harbor. The plant’s future is in question after a scheme for ratepayers to subsidize it was repealed after the exposure of corruption in the legislation process. Read more. (Photo by dkniselyderivative work: kaʁstn Disk/Cat, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

After thousands of doors, I realized that talking about the need to protect our beloved lake was the most effective way of garnering support. The more someone told me of their direct experience on the lake (I take my child fishing, we visit the islands every year, etc.) the more likely they were to donate. It was actually love, not fear, that motivated people to give us money and write letters for the cause.

We protect what we love, and we have to know something to love it. At the meeting of the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1968, the Senegalese poet Baba Dioum expressed this sentiment best: “In the end, we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught." In the absence of a land-based cultural inheritance, we must take responsibility for teaching ourselves about the land, a truly lifelong process. The outcome of the exercise of crafting a sense of place is not just for me, it’s also for the benefit of the larger ecosystem. Or maybe there is no distinction. Considering Gaian wholeness, what is the lake if not an extension of myself?

In October 1998, as this new term came into common parlance in green circles, Agraria, then known as Community Service, Inc., held a conference titled, “Nurturing a Sense of Place.” “Upon the human capacity for nurturing a true sense of place may depend the fate of the Earth,” wrote Yellow Springs News editor Don Wallis in his coverage of the event. “For without a sense of place — a deeply felt awareness that here, where we are, is where we belong — there can be no real sense of community, or of health, or of ecology, or of peace.”

According to the article, visionary ecologist Stephanie Mills shared that to nurture a sense of place, “is to reclaim the possibility of natural richness and human wholeness,” which she said was essential to avoid the rapid extinction that was annihilating the planet’s biodiversity. For that, she said, the world needs “people skilled in the arts of place and working in community” to develop “place-sensitive and place-expressive communities.”

A sense of place “has got to become keen in us again,” Mills said. “We need a sense of place to safeguard the Creation.”

In a recent Zoom call, 24 years later, Mills reiterated that, to her, the term sense of place is about “loyalty to place; connection, and responsibility for, a specific place.” Today, though, she acknowledges that the characteristics of place are far more dynamic, in flux, due to climate changes and the resulting movement of species. It’s also, like many good ideas, become co-opted and commercialized, used in corporate marketing like real estate ads.

“I’m all for reclaiming it,” she added.

Back in 1998, Wallis reported a reflection from attendee Lisa Landess that while the conference was clearly “for the planet,” it felt like trying to save the planet seemed “too overpowering, too overwhelming a task.”

Landess, Wallis wrote, mused on a “middle way.”

“Maybe we have to admit that we haven’t found the answer to the dilemma of progress. Maybe the key is for everyone to become aware of their own little place on Earth, to identify with it, to act on its behalf. That’s something that is important, and something we can do.”

*Bachman is the assistant director of the Agraria Center for Regenerative Practice. She can be reached at: mbachman@communitysolution.org.

A cottonwood tree that long stood at the edge of land and lake at Huntington Beach, Bay Village, Ohio. (Photo by Erik Drost, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)