Thinking Big to Protect Water and Habitat

The Birch Creek watershed encompasses a much larger area than the section of Birch Creek that flows through Glen Helen.

By Nick Boutis

Conservationists sometimes frame wildlife management in terms of “Keystone Species” and “Umbrella Species.” The idea is straightforward enough: A keystone is found at the top of a stone arch. Without it, the arch will not stand. Similarly, a keystone species is one that is essential to the continued function of its ecosystem. Likewise, an umbrella protects all that is below it. Ergo, when you protect an umbrella species you protect the entire ecosystem.

Water resources for an ecosystem can be thought of as both the keystone and the umbrella. If you lose the water resources, you lose the entire ecosystem that depends on it. If you protect the water resources, you protect the entire ecosystem.

And yet, water is often peripheral to our thinking about protecting habitats. When you think about our country’s parks and preserves, rarely (dare I say never?) is the preserve boundary designed to encompass an entire watershed. Lots of parks protect mountains or caves or deserts or maybe, as is the case with Glen Helen, a thin stretch of land a half mile wide, by four miles long. Preserve boundaries tend to be political, or visual, or geographic. I cannot think of a single example where a park boundary is defined by its watershed. Ultimately, what this means is that water flows into protected lands upstream from who-knows-where, and exits protected lands downstream to who-knows-where.

In the early 1960s, one of my predecessors, Ken Hunt, had a vision for better protecting the land around Glen Helen and its neighbors, John Bryan State Park and Clifton Gorge State Nature Preserve. Ken and his co-conspirators imagined a triangle bordered by State Route 343, Clifton Road, and what is now the Little Miami Bike Trail. They named this triangle the “Country Commons.” The idea was that, if all of the property owners within this triangle would be willing to accept a conservation easement on their property, it would create a protected area that would safeguard Glen Helen and the state lands from encroachment and “conserve open space and natural beauty for the use, inspiration, and enjoyment of all men.”

For 60 years, we more or less pursued this vision. When the Glen Helen Association acquired Camp Greene from the Girl Scouts of Western Ohio, it was with the idea that not only was the former camp adjacent to Glen Helen on the Little Miami River, it was also a core (and vulnerable) parcel within the Country Commons. A couple of years later, we were able to work with the children of Barbara and David Case to acquire their wonderful 46-acre homestead off State Route 343. It was a hugely important parcel for us because of its proximity to the Outdoor Education Center; it was also within the Country Commons.

Then, we turned our attention to the Sutton Farm just north of the Glen, across the road from the Outdoor Education Center. Owned by the Village of Yellow Springs, much of the land was leased to an area farmer who annually planted a soybean crop using conventional growing techniques. We liked the idea of instead managing that land as forest contiguous to the Glen, but what really interested us in the property was that Birch Creek flowed through the Sutton Farm before crossing under the road and into the Glen. If we could better protect a longer stretch of Birch Creek, then we could ensure cleaner water and healthier habitats along the creek. Now, instead of thinking about a protected area bordered by roads, we for the first time gave consideration to what the Glen’s watershed looked like.

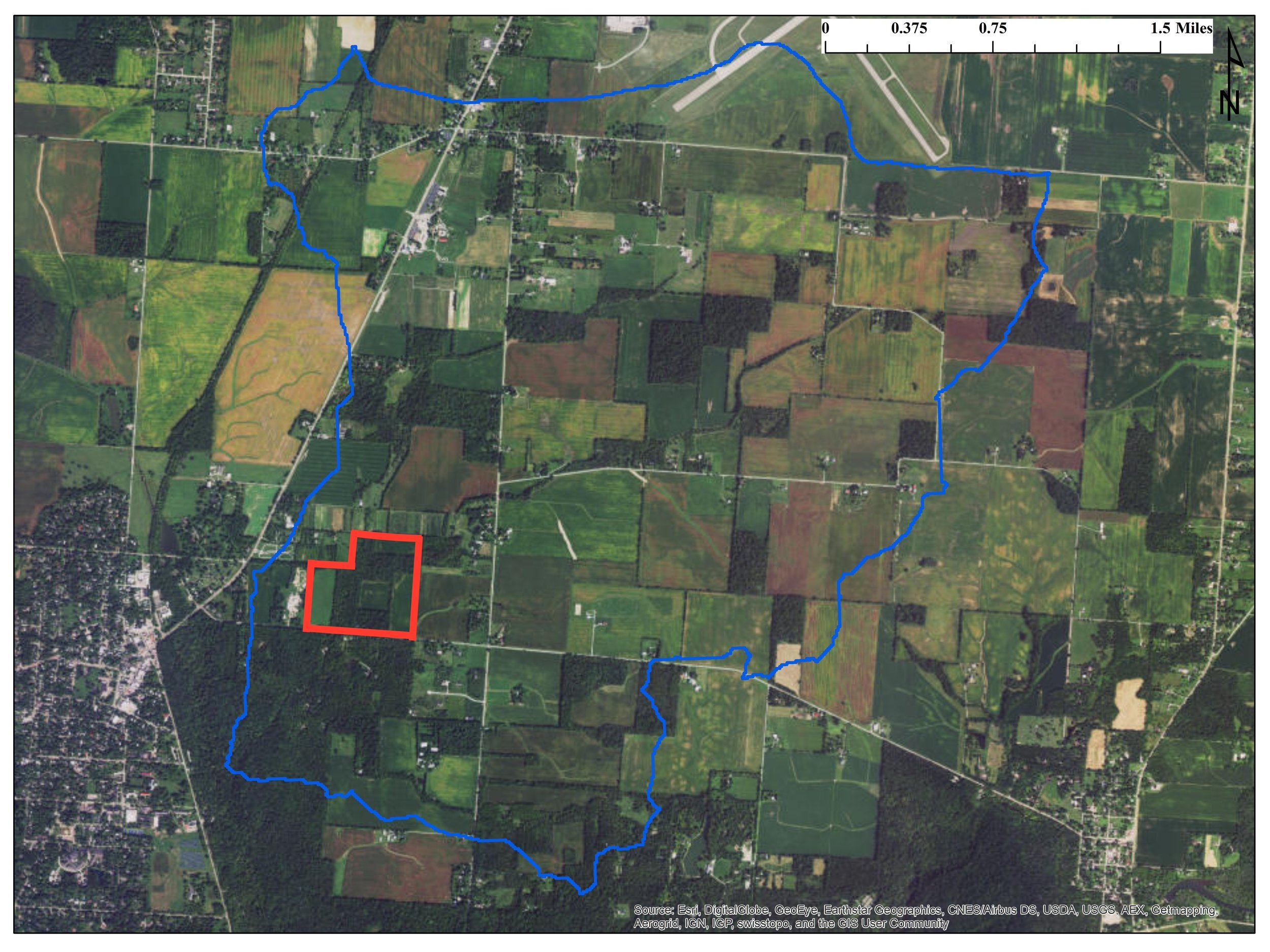

We honestly were not prepared for what we learned. The accompanying map shows the Sutton Farm outlined in red and the Birch Creek watershed in blue. At the lower left, you see the village of Yellow Springs, Ohio, with the forests of Glen Helen immediately to its right. Analyzing the map, we realized that only about 8% of the Birch Creek watershed is in Glen Helen. Put another way, 92% of the water that flows over the Cascades in the Glen is coming from neighboring farmland or homesteads, Young’s Jersey Dairy, and the Springfield Air National Guard base.

We could follow every best practice for stewarding the water resources within the Glen, but the water quality in the preserve would still be largely determined by the choices made by our upstream neighbors. The same is true for the other watersheds the Glen is part of, principally the Yellow Springs Creek and the Little Miami River.

We realized we had a management dilemma that we hadn’t previously given much thought to: How do we protect Glen Helen if we don’t control the water, and, how do we influence the quality of the water if we don’t own the land? Here is where I would love to say that there was a simple solution, a problem solved, and a happy ending. Alas, environmental challenges rarely work out that tidily.

Still, we know what the basic parameters of a solution are:

There may be some lands in our watershed that it makes sense for us to try to acquire. We’ve added 150 acres to the Glen over the past 10 years and, in time, we may have the opportunity to add more. Of course, this gets expensive, both because of the purchase price, and because it takes time and effort to manage land. But land acquisition has a big advantage: we can manage the land we own with a priority placed on ecological stewardship rather than some other competing interest.

We may also be able to work with our neighbors and our friends at the Tecumseh Land Trust to see that lands upstream are protected by conservation easements, allowing agriculture to continue, but ensuring that these lands are not subdivided and developed. Indeed, many of the parcels near and adjacent to Glen Helen are already in the land trust. We can’t expect that these neighbors will manage their lands as a natural area, but we can count on them maintaining the conservation values of the land as articulated in their conservation easements.

For most of the property owners who live upstream, however, we will ultimately rely on education to make people aware that they are part of the Glen Helen watershed and that the decisions they make on their property will impact the health of the preserve and everything downstream. Moreover, there are actions they can take to help ensure that the water coming into the Glen is as high quality as possible.

One parting example: one of the noxious species in the Glen is Lesser Celandine. Highly, highly invasive, it spreads downstream along creeks. When we identified this plant along the Yellow Springs Creek, we went looking upstream, and found infestations of it in neighborhoods in the town. In backyards in Yellow Springs, tubers from the plant were breaking off, floating downstream, and gaining a foothold in the Glen. We started connecting with homeowners in town, to make them aware of what Lesser Celandine looks like and working with them to eliminate it on their property, both to protect their own land and to protect the Glen.

Along the way, our neighbors gain a better understanding that they are part of the Glen Helen watershed and that the way they manage their yard will impact the health of the preserve. Runoff is still carrying Lesser Celandine into the preserve, but awareness among our upstream neighbors is growing, and each year, more property owners redouble their efforts to tackle what’s in their own backyard.

Nick Boutis is executive director of Glen Helen Nature Preserve.